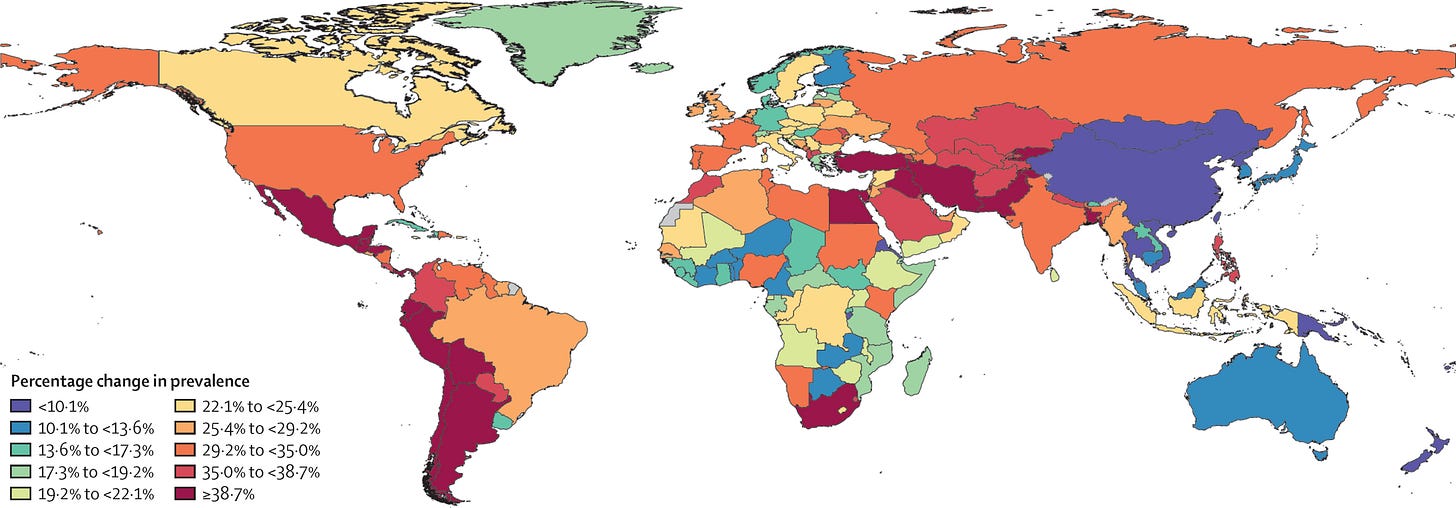

We live in the midst of an unprecedented mental health crisis. Around the world, suicide rates climb alongside depression and mental illness, while social isolation deepens, trust in institutions erodes, and anxiety disorders reach epidemic proportions. According to WHO data, the COVID-19 pandemic triggered a 25% increase in the global prevalence of anxiety and depression during the first year of the pandemic1.

Multiple forces have converged to foster this moment: the erosion of democratic institutions, climate catastrophe, the neoliberalization of the economy, and perhaps most fundamentally, what philosopher John Vervaeke calls the "meaning crisis", a profound disconnection from ourselves, from others, from the planet, and from any coherent vision of the future2. In a way, the future itself has been canceled, returning now, as Mark Fisher observed, only to haunt us3.

This crisis of meaning represents more than individual psychological distress. It signals a civilizational rupture where the very sources from which humans have traditionally derived purpose and identity are being systematically undermined.

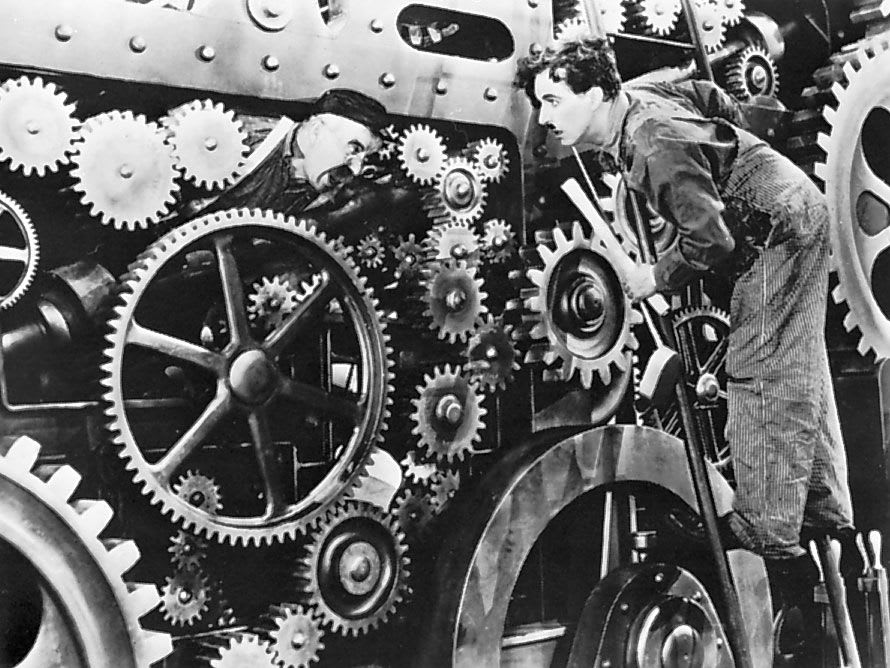

Adding to the camel's back, the emergence of artificial intelligence threatens to accelerate this meaning crisis exponentially. Where previous waves of automation primarily displaced manual labor, AI systems now encroach upon the domains we once considered uniquely human: creativity, analysis, judgment, and even care. This represents what Bernard Stiegler identified as a new phase of "generalized proletarianization", not merely the loss of manual skill that Marx observed with industrial workers, but the externalization and automation of our cognitive and emotional capacities themselves4.

The Problem with AI

When AI can write sophisticated code, compose emotionally resonant music, diagnose complex illnesses, and offer nuanced psychological counsel, often at standards matching or exceeding human performance, we face fundamental questions about human purpose and value. The meaning crisis intensifies because AI doesn't simply replace human functions, it calls into question the very activities through which we have traditionally constructed meaning and identity.

I find Nobel laureate Amartya Sen's work on human development to be helpful here. Sen famously observed that people in Bangladesh often report higher levels of happiness and demonstrate longer life expectancy than residents of the Bronx, New York, despite vast differences in material wealth. This paradox led him to develop the capability approach, which argues that human wellbeing depends not on utility maximization or resource accumulation alone, but on our capabilities: our real freedoms to achieve valuable functionings in life5.

AI threatens these foundational capabilities in three interconnected ways that traditional automation never could.

1. Comprehensive Job Displacement

First, through job displacement that extends far beyond manual labor into knowledge work, creative industries, and care professions. It is clear that AI will eliminate more jobs than it will create. McKinsey projects 400-800 million jobs globally affected by 2030. Furthermore, AI undermines not just income but the capability to participate meaningfully in social and economic life. This is not simply unemployment but the further expansion of “bullshit jobs” across the board.

2. Outsourced Responsibility

Beyond job displacement, AI threatens to become the ultimate scapegoat for corporate decisions that harm human wellbeing. Mass layoffs can now be blamed on AI. Exploitative labor practices (Cf. Silicon Valley's newfound interest in the 9-9-6 schedule) are justified as necessary responses to AI competition. Institutional bias in hiring and lending gets laundered through "objective" algorithms.

In this sense, AI functions as the new McKinsey: a prestigious external authority brought in to legitimize decisions that management wanted to make anyway, while helping them avoid responsibility for the human consequences. Joseph Weizenbaum, creator of ELIZA (the first chatbot) warned of precisely this danger in the 1970s, foreseeing how computational systems would allow powerful institutions to hide behind the veil of algorithmic objectivity6.

3. Capability Atrophy

Third, and more insidiously, AI systems promote what we might call "capability atrophy." When we outsource cognitive tasks to AI (from navigation to writing to decision-making) we lose the very capabilities that Sen identifies as crucial for human flourishing. This creates a vicious cycle: as our capabilities diminish, we become more dependent on AI systems, further eroding our autonomy and agency and turning us into what Shoshana Zuboff called “Functional Idiots”7. The learned helplessness this engenders represents a fundamental assault on human dignity.

Consider how GPS navigation has already atrophied our spatial reasoning capabilities, or how autocomplete functions diminish our capacity for linguistic precision. AI promises to extend this atrophy across the full spectrum of human cognition, from mathematical reasoning to emotional intelligence and critical thinking.

Accelerated Intelligence or Ignorance?

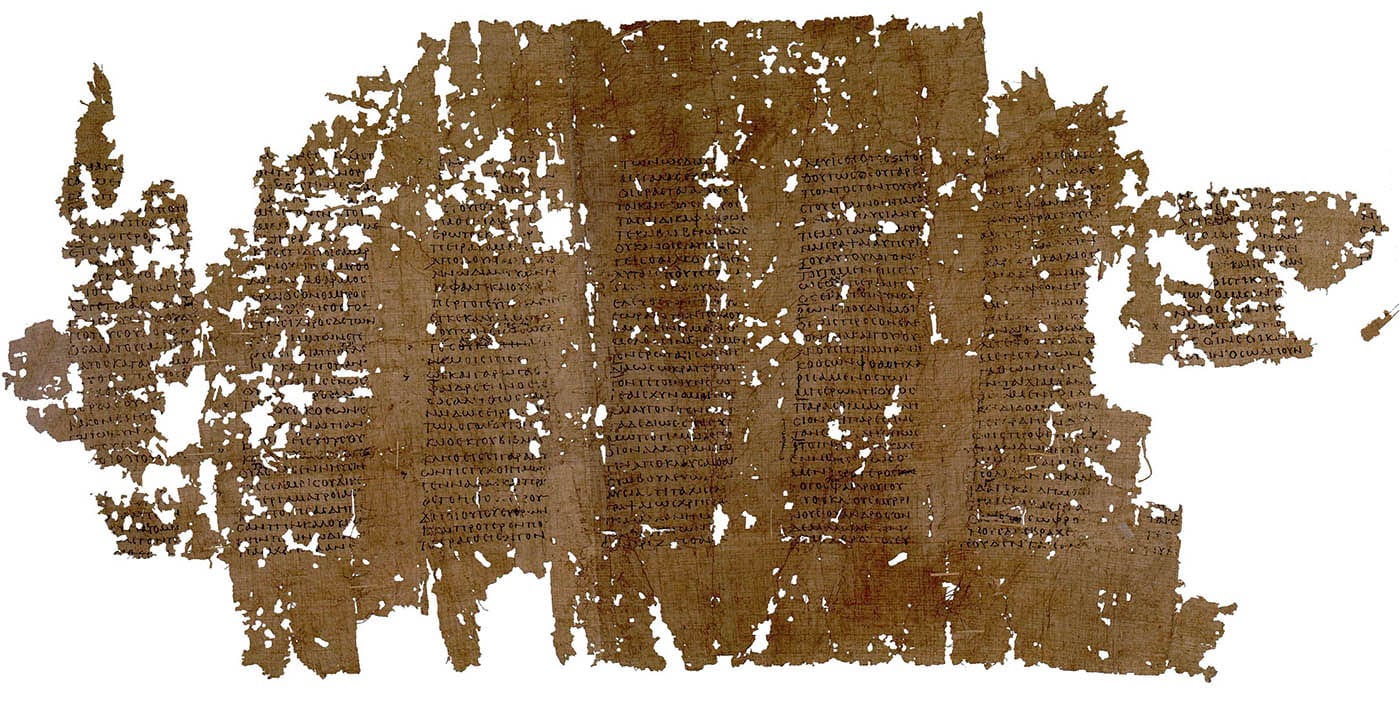

We've seen this before. In Plato's Phaedrus, Socrates tells the story of the Egyptian god Theuth presenting writing to King Thamus as a gift to enhance human memory. Thamus rejects it, warning that writing will "create forgetfulness in learners' souls" as they rely on external marks rather than internal memory. People will "seem to know many things" while possessing only superficial understanding8. Today, as we outsource ever more cognitive functions to AI, Thamus's prophecy finds new relevance. Just as writing transformed memory from an internal capacity to an external crutch, LLMs threaten to transform thinking itself into something we witness rather than perform.

History proved Thamus both right and wrong. Yes, we lost our prodigious memories, but we gained libraries, literature, and the accumulated wisdom of civilizations. Similarly, AI offers undeniable benefits. It democratizes access to knowledge, accelerates scientific discovery, and eliminates cognitive drudgery. A student in rural Algeria can access world-class tutoring; a doctor can diagnose rare diseases better, and an entrepreneur can build a business that can compete globally in a matter of days.

Yet AI's reach extends far beyond writing's. Where writing externalized memory, AI seeks to externalize our capacity to think, create, and imagine. This colonization of the human soul is unprecedented in scope and unprecedented in scale.

The result? AI will continue to erode the capabilities of ever-larger segments of society. The meaning crisis will deepen as more people find themselves trapped in a world where their distinctively human contributions feel increasingly obsolete.

Perhaps Warren Bennis was right in his prediction that the factory of the future will have only two employees, a man and a dog. The man will be there to feed the dog. The dog will be there to keep the man from touching the equipment.

What we can do about it

Fortunately, the story need not end in despair. Both Stiegler and Sen point toward possibilities for human flourishing even within technological societies. The key insight is that AI, paradoxically, creates both the problem and the potential solution: while it threatens to erode our capabilities, it also generates what Clay Shirky called a "cognitive surplus", freed time and intellectual capacity we collectively gain through technological efficiency9.

This cognitive surplus represents perhaps one of the most important political questions of our time: how do we reclaim and direct it toward expanding our capabilities rather than further dependency?

1. Reclaim our cognitive surplus for good

AI can amplify human capabilities when we maintain conscious control over the relationship, but it atrophies them when we surrender agency to automated systems.

I have personally experienced this dynamic. The emergence of AI tools to assist with research, writing and editing, allowed me to open up this substack and write more often.

There genuinely has never been a better time to pursue passion projects or learn new skills. Everything from cuisine to crafts, from philosophy to physics, is accessible. One can easily imagine a world of cross-pollination where the artificial boundaries between disciplines dissolve. AI + the cognitive surplus it engenders could close the digital & information gap for everyone once and for all.

2. Weave Communities

Naturally, these individual strategies cannot succeed in isolation. Our humanity is irreducibly social, it emerges from our shared sense of purpose, our networked relationships, and our collective engagement with the world. The meaning crisis is first and foremost an isolation crisis. The battle against AI-induced proletarianization must be fought collectively, through communities that actively cultivate human capabilities.

Instead of Utopias, we need to cultivate heterotopias to achieve this10. We need physical and social environments where different practices of human development can thrive. We already see these emerging in hackerspaces, makerspaces, bicycle repair cooperatives, community gardens, and countless other initiatives where people gather to develop capabilities that complement rather than compete with AI systems: embodied skills, social coordination, creative problem-solving, and the kind of contextual wisdom that emerges from face-to-face collaboration.

3. Distribute AI dividend fairly

In the end, these individual and collective responses operate within a fundamentally political context. The question of what to do with AI's cognitive surplus is inseparable from the question of what to do with AI's economic surplus. Should the productivity gains from AI flow primarily to shareholders, or should they be distributed more broadly to workers and communities?

These distributions are not inevitable, they are negotiable political arrangements. The productivity gains from AI could flow back to people through various mechanisms: universal basic income, capability vouchers that help individuals develop new skills, job guarantee programs, or other policies that break the current winner-takes-all dynamic.

Beyond merely boosting global GDP, AI has the transformational potential to shrink the global Gini coefficient.

Conclusion

If happiness is indeed our goal, the current trajectory suggests AI will not deliver it. Quite the opposite. AI will certainly further erode human capabilities and extend proletarianization to larger segments of society if we allow market forces and technological determinism to shape its development unchecked. But there are alternative arrangements—individual, collective, and political—that could redirect AI's effects toward human flourishing.

When reading Phaedrus Dialogue, Algeria-born philosopher Derrida saw something deeper: writing is a pharmakon, simultaneously cure and poison, helper and threat11.

Building on Derrida’s insight, I believe AI is the ultimate pharmakon. It promises to both “supplement” human intelligence and threatens to supplant it entirely. Like all supplements, AI reveals an uncomfortable truth: perhaps human thinking was never as autonomous as we imagined. Perhaps we were always already cyborgs12, dependent on cognitive technologies from language to writing to generative intelligence today.

The question isn't whether to accept or reject AI, the pharmakon cannot be simply embraced or expelled. The challenge is to learn how to live with this powerful supplement (and its both/and logic) without letting it consume what it was meant to enhance, even when doing so creates friction and discomfort in the short term.

This requires care: care for ourselves through practices that maintain our cognitive autonomy, care for others through communities where we develop irreplaceable human capabilities, and care for the future through a politics that puts people and planet over profit. Only then can we ensure that AI enhances rather than diminishes the human capacity for meaning, purpose, and yes—happiness.

Notes & Further Reading

Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic Santomauro, Damian F et al. The Lancet, Volume 398, Issue 10312, 1700 - 1712

John Vervaeke, "Awakening from the Meaning Crisis" (YouTube lecture series, 2019) - 50-episode deep dive into meaning, cognition, and wisdom

Fisher, Mark. "What Is Hauntology?" Film Quarterly, vol. 66, no. 1, 2012, pp. 16-24, https://doi.org/10.1525/fq.2012.66.1.16.

Stiegler, Bernard. Automatic Society, Volume 1: The Future of Work. Translated by Daniel Ross, Polity Press, 2016.

Sen, Amartya. Development as Freedom. Anchor Books, 1999.

Weizenbaum, Joseph. Computer Power and Human Reason: From Judgment to Calculation. W. H. Freeman, 1976.

Zuboff, Shoshana. The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power. PublicAffairs, 2019.

Plato. Phaedrus. Translated by R. Hackforth, Cambridge University Press, 1952.

Shirky, Clay. Cognitive Surplus: Creativity and Generosity in a Connected Age. Penguin Press, 2010.

Foucault, Michel. "Of Other Spaces: Utopias and Heterotopias." Translated by Jay Miskowiec, Diacritics, vol. 16, no. 1, Spring 1986, pp. 22-27.

Derrida, Jacques. "Plato's Pharmacy." Dissemination, translated by Barbara Johnson, University of Chicago Press, 1981, pp. 61-171.

Haraway, Donna J. "A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century." Simians, Cyborgs, and Women: The Reinvention of Nature, Routledge, 1991, pp. 149-181.